PART 8

.

Gibbon, in his inimitable way, has drawn the youth's portrait: His passions were strong; his understanding was feeble; and he was intoxicated with a foolish pride . . . His favourite ministers were two beings the least susceptible of human sympathy, a eunuch and a monk; the former corrected the emperor's mother with a scourge, the latter suspended the insolvent tributaries, with their heads downwards, over a slow and smoky fire.

After ten years of intolerable misrule there was a revolution, and the new Emperor, Leontius, ordered Justinian's mutilation and banishment: The amputation of his nose, perhaps of his tongue, was imperfectly performed; the happy flexibility of the Greek language could impose the name of Rhinotmetus ("Cut-off Nose"); and the mutilated tyrant was banished to Chersonae in Crim-Tartary, a lonely settlement where corn, wine and oil were imported as foreign luxuries. (The treatment meted out to Justinian was actually regarded as an act of leniency: the general tendency of the period was to humanize the criminal law by substituting mutilation for capital punishment – amputation of the hand [for thefts] or nose [fornication, etc], being the most frequent form. Byzantine rulers were also given to the practice of blinding dangerous rivals, while magnanimously sparing their lives).

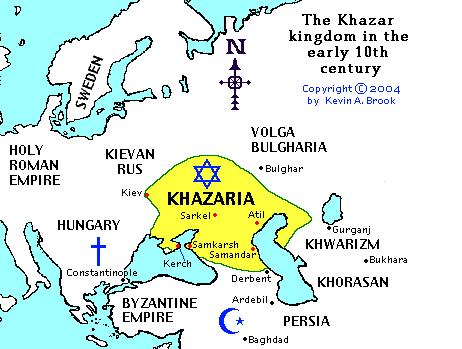

During his exile in Cherson, Justinian kept plotting to regain his throne. After three years he saw his chances improving when, back in Byzantium, Leontius was de-throned and also had his nose cut off. Justinian escaped from Cherson into the Khazar-ruled town of Doros in the Crimea and had a meeting with the Kagan of the Khazars, King Busir or Bazir. The Kagan must have welcomed the opportunity of putting his fingers into the rich pie of Byzantine dynastic policies, for he formed an alliance with Justinian and gave him his sister in marriage. This sister, who was baptized by the name of Theodora, and later duly crowned, seems to have been the only decent person in this series of sordid intrigues, and to bear genuine love for her noseless husband (who was still only in his early thirties. The couple and their band of followers were now moved to the town of Phanagoria (the present Taman) on the eastern shore of the strait of Kerch, which had a Khazar governor.

Here they made preparations for the invasion of Byzantium with the aid of the Khazar armies which King Busir had apparently promised. But the envoys of the new Emperor, Tiberias III, persuaded Busir to change his mind, by offering him a rich reward in gold if he delivered Justinian, dead or alive, to the Byzantines. King Busir accordingly gave orders to two of his henchmen, named Papatzes and Balgitres, to assassinate his brother-in-law. But faithful Theodora got wind of the plot and warned her husband. Justinian invited Papatzes and Balgitres separately to his quarters, and strangled each in turn with a cord. Then he took ship, sailed across the Black Sea into the Danube estuary, and made a new alliance with a powerful Bulgar tribe. Their king, Terbolis, proved for the time being more reliable than the Khazar Kagan, for in 704 he provided Justinian with 15000 horsemen to attack Constantinople. The Byzantines had, after ten years, either forgotten the darker sides of Justinian's former rule, or else found their present ruler even more intolerable, for they promptly rose against Tiberias and reinstated Justinian on the throne. The Bulgar King was rewarded with "a heap of gold coin which he measured with his Scythian whip" and went home (only to get involved in a new war against Byzantium a few years later).

Justinian's second reign (704-711) proved even worse than the first; "he considered the axe, the cord and the rack as the only instruments of royalty". He became mentally unbalanced, obsessed with hatred against the inhabitants of Cherson, where he had spent most of the bitter years of his exile, and sent an expedition against the town.

Some of Cherson's leading citizens were burnt alive, others drowned, and many prisoners taken, but this was not enough to assuage Justinian's lust for revenge, for he sent a second expedition with orders to raze the city to the ground. However, this time his troops were halted by a mighty Khazar army; whereupon Justinian's representative in the Crimea, a certain Bardanes, changed sides and joined the Khazars. The demoralized Byzantine expeditionary force abjured its allegiance to Justinian and elected Bardanes as Emperor, under the name of Philippicus. But since Philippicus was in Khazar hands, the insurgents had to pay a heavy ransom to the Kagan to get their new Emperor back. When the expeditionary force returned to Constantinople, Justinian and his son were assassinated and Philippicus, greeted as a liberator, was installed on the throne only to be deposed and blinded a couple of years later.

The point of this gory tale is to show the influence which the Khazars at this stage exercised over the destinies of the East Roman Empire – in addition to their role as defenders of the Caucasian bulwark against the Muslims. Bardanes - hilippicus was an emperor of the Khazars' making, and the end of Justinian's reign of terror was brought about by his brotherin - law, the Kagan. To quote Dunlop: "It does not seem an exaggeration to say that at this juncture the Khaquan was able practically to give a new ruler to the Greek empire."

The point of this gory tale is to show the influence which the Khazars at this stage exercised over the destinies of the East Roman Empire – in addition to their role as defenders of the Caucasian bulwark against the Muslims. Bardanes - hilippicus was an emperor of the Khazars' making, and the end of Justinian's reign of terror was brought about by his brotherin - law, the Kagan. To quote Dunlop: "It does not seem an exaggeration to say that at this juncture the Khaquan was able practically to give a new ruler to the Greek empire."

PART 9

From the chronological point of view, the next event to be discussed should be the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism, around AD 740. But to see that remarkable event in its proper perspective, one should have at least some sketchy idea of the habits, customs and everyday life among the Khazars prior to the conversion. Alas, we have no lively eyewitness reports, such as Priscus's description of Attila's court.

What we do have are mainly second-hand accounts and compilations by Byzantine and Arab chroniclers, which are rather schematic and fragmentary – with two exceptions. One is a letter, purportedly from a Khazar king, to be discussed in Chapter 2; the other is a travelogue by an observant Arab traveller, Ibn Fadlan, who – like Priscus – was a member of a diplomatic mission from a civilized court to the Barbarians of the North.

The court was that of the Caliph al Muktadir, and the diplomatic mission travelled from Baghdad through Persia and Bukhara to the land of the Volga Bulgars. The official pretext for this grandiose expedition was a letter of invitation from the Bulgar king, who asked the Caliph (a) for religious instructors to convert his people to Islam, and (b) to build him a fortress which would enable him to defy his overlord, the King of the Khazars. The invitation – which was no doubt prearranged by earlier diplomatic contacts – also provided an opportunity to create goodwill among the various Turkish tribes inhabiting territories through which the mission had to pass, by preaching the message of the Koran and distributing huge amounts of gold bakhshish.

The opening paragraphs of our traveller's account read (The following quotations are based on Zeki Validi Togan's German translation of the Arabic text and the English translation of extracts by Blake and Frye, both slightly paraphrased in the interest of readability): This is the book of Ahmad ibn-Fadlan ibn-al-Abbas, ibn-Rasid, ibn-Hammad, an official in the service of [General] Muhammed ibn-Sulayman, the ambassador of [Caliph] al Muktadir to the King of the Bulgars, in which he relates what he saw in the land of the Turks, the Khazars, the Rus, the Bulgars, the Bashkirs and others, their varied kinds of religion, the histories of their kings, and their conduct in many walks of life.

The letter of the King of the Bulgars reached the Commander of the Faithful, al Muktadir; he asked him therein to send him someone to give him religious instruction and acquaint him with the laws of Islam, to build him a mosque and a pulpit so that he may carry out his mission of converting the people all over his country; he also entreated the Caliph to build him a fortress to defend himself against hostile kings (i.e., as later passages show, the King of the Khazars). Everything that the King asked for was granted by the Caliph. I was chosen to read the Caliph's message to the King, to hand over the gifts the Caliph sent him, and to supervise the work of the teachers and interpreters of the Law . . . (].There follow some details about the financing of the mission and names of participants.] And so we started on Thursday the 11th Safar of the year 309 [June 21, AD 921) from the City of Peace [Baghdad, capital of the Caliphate

The date of the expedition, it will he noted, is much later than the events described in the previous section. But as far as the customs and institutions of the Khazars' pagan neighbours are concerned, this probably makes not much difference; and the glimpses we get of the life of these nomadic tribes convey at least some idea of what life among the Khazars may have been during that earlier period – before the conversion – when they adhered to a form of Shamanism similar to that still practised by their neighbours in Ibn Fadlan's time.

The progress of the mission was slow and apparently uneventful until they reached Khwarizm, the border province of the Caliphate south of the Sea of Aral.

Here the governor in charge of the province tried to stop them from proceeding further by arguing that between his country and the kingdom of the Bulgars there were "a thousand tribes of disbelievers" who were sure to kill them. In fact his attempts to disregard the Caliph's instructions to let the mission pass might have been due to other motives: he realized that the mission was indirectly aimed against the Khazars, with whom he maintained a flourishing trade and friendly relations. In the end, however, he had to give in, and the mission was allowed to proceed to Gurganj on the estuary of the Amu-Darya. Here they hibernated for three months, because of the intense cold – a factor which looms large in many Arab travellers' tales:

The river was frozen for three months, we looked at the landscape and thought that the gates of the cold Hell had been opened for us. Verily I saw that the market place and the streets were totally empty because of the cold . . . Once, when I came out of the bath and got home, I saw that my beard had frozen into a lump of ice, and I had to thaw it in front of the fire. I stayed for some days in a house which was inside of another house [compound?] and in which there stood a Turkish felt tent, and I lay inside the tent wrapped in clothes and furs, but nevertheless my cheeks often froze to the cushion . . . Around the middle of February the thaw set in.

The mission arranged to join a mighty caravan of 5000 men and 3000 pack animals to cross the northern steppes, and bought the necessary supplies: camels, skin boats made of camel hides for crossing rivers, bread, millet and spiced meat for three months. The natives warned them about the even more frightful cold in the north, and advised them what clothes to wear: So each of us put on a Kurtak, [camisole] over that a woollen Kaftan, over that a buslin, [fur-lined coat] over that a burka [fur coat]; and a fur cap, under which only the eyes could be seen; a simple pair of underpants, and a lined pair, and over them the trousers; house shoes of kaymuht [shagreen leather] and over these also another pair of boots; and when one of us mounted a camel, he was unable to move because of his clothes.

Ibn Fadlan, the fastidious Arab, liked neither the climate nor the people of Khwarizm: They are, in respect of their language and constitution, the most repulsive of men. Their language is like the chatter of starlings. At a day's journey there is a village called Ardkwa whose inhabitants are called Kardals; their language sounds entirely like the croaking of frogs.

They left on March 3 and stopped for the night in a caravanserai called Zamgan – the gateway to the territory of the Ghuzz Turks. From here onward the mission was in foreign land, "entrusting our fate to the all-powerful and exalted God". During one of the frequent snowstorms, Ibn Fadlan rode next to a Turk, who complained: "What does the Ruler want from us? He is killing us with cold. If we knew what he wants we would give it to him." Ibn Fadlan: "All he wants is that you people should say: "There is no God save Allah". The Turk laughed: "If we knew that it is so, we should say so."

There are many such incidents, which Ibn Fadlan reports without appreciating the independence of mind which they reflect. Nor did the envoy of the Baghdad court appreciate the nomadic tribesmen's fundamental contempt for authority. The following episode also occurred in the country of the powerful Ghuzz Turks, who paid tribute to the Khazars and, according to some sources, were closely related to them: The next morning one of the Turks met us. He was ugly in build, dirty in appearance, contemptible in manners, base in nature; and we were moving through a heavy rain. Then he said: "Halt." Then the whole caravan of 3000 animals and 5000 men halted. Then he said: "Not a single one of you is allowed to go on."

We halted then, obeying his orders. (Obviously the leaders of the great caravan had to avoid at all costs a conflict with the Ghuzz tribesmen). Then we said to him: "We are friends of the Kudarkin [Viceroy]". He began to laugh and said: "Who is the Kudarkin? I shit on his beard." Then he said: "Bread." I gave him a few loaves of bread. He took them and said: "Continue your journey; I have taken pity on you."

The democratic methods of the Ghuzz, practised when a decision had to be taken, were even more bewildering to the representative of an authoritarian theocracy: They are nomads and have houses of felt. They stay for a while in one place and then move on. One can see their tents dispersed here and there all over the place according to nomadic custom. Although they lead a hard life, they behave like donkeys that have lost their way. They have no religion which would link them to God, nor are they guided by reason; they do not worship anything. Instead, they call their headmen lords; when one of them consults his chieftain, he asks: “O lord, what shall I do in this or that matter?” The course of action they adopt is decided by taking counsel among themselves; but when they have decided on a measure and are ready to carry it through, even the humblest and lowliest among them can come and disrupt that decision.

The sexual mores of the Ghuzz – and other tribes – were a remarkable mixture of liberalism and savagery: Their women wear no veils in the presence of their men or strangers. Nor do the women cover any parts of their bodies in the presence of people. One day we stayed at the place of a Ghuzz and were sitting around; his wife was also present. As we conversed, the woman uncovered her private parts and scratched them, and we all saw it. Thereupon we covered our faces and said: “May God forgive me.” The husband laughed and said to the interpreter: Tell them we uncover it in your presence so that you may see and restrain yourselves; but it cannot be attained. This is better than when it is covered up and yet attainable.” Adultery is alien to them; yet when they discover that someone is an adulterer they split him in two halves. This they do by bringing together the branches of two trees, tie him to the branches and then let both trees go, so that the man tied to them is torn in two. He does not say whether the same punishment was meted out to the guilty woman. Later on, when talking about the Volga Bulgars, he describes an equally savage method of splitting adulterers into two, applied to both men and women. Yet, he notes with astonishment, Bulgars of both sexes swim naked in their rivers, and have as little bodily shame as the Ghuzz.

As for homosexuality – which in Arab countries was taken as a matter of course – Ibn Fadlan says that it is “regarded by the Turks as a terrible sin”. But in the only episode he relates to prove his point, the seducer of a “beardless youth” gets away with a fine of 400 sheep.

Accustomed to the splendid baths of Baghdad, our traveller could not get over the dirtiness of the Turks. “The Ghuzz do not wash themselves after defacating or urinating, nor do they bathe after seminal pollution or on other occasions. They refuse to have anything to do with water, particularly in winter . . .”. When the Ghuzz commander-in-chief took off his luxurious coat of brocade to don a new coat the mission had brought him, they saw that his underclothes were “faying apart from dirt, for it is their custom never to take off the garment they wear close to their bodies until it disintegrates”. Another Turkish tribe, the Bashkirs,“ shave their beards and eat their lice. They search the folds of their undergarments and crack the lice with their teeth”. When Ibn Fadlan watched a Bashkir do this, the latter remarked to him: “They are delicious”.

All in all, it is not an engaging picture. Our fastidious traveller's contempt for the barbarians was profound. But it was only aroused by their uncleanliness and what he considered as indecent exposure of the body; the savagery of their punishments and sacrificial rites leave him quite indifferent. Thus he describes the Bulgars' punishment for manslaughter with detached interest, without his otherwise frequent expressions of indignation: "They make for him [the delinquent] a box of birchwood, put him inside, nail the lid on the box, put three loaves of bread and a can of water beside it, and suspend the box between two tall poles, saying: "We have put him between heaven and earth, that he may be exposed to the sun and the rain, and that the deity may perhaps forgive him." And so he remains suspended until time lets him decay and the winds blow him away."

He also describes, with similar aloofness, the funeral sacrifice of hundreds of horses and herds of other animals, and the gruesome ritual killing of a Rus (Rus: the Viking founders of the early Russian settlements – see below, Chapter III.) slave girl at her master's bier.

About pagan religions he has little to say. But the Bashkirs' phallus cult arouses his interest, for he asks through his interpreter one of the natives the reason for his worshipping a wooden penis, and notes down his reply: "Because I issued from something similar and know of no other creator who made me." He then adds that 'some of them [the Bashkirs] believe in twelve deities, a god for winter, another for summer, one for the rain, one for the wind, one for the trees, one for men, one for the horse, one for water, one for the night, one for the day, a god of death and one for the earth; while that god who dwells in the sky is the greatest among them, but takes counsel with the others and thus all are contented with each other's doings.

Phallus Worship

. . We have seen a group among them which worships snakes, and a group which worships fish, and a group which worships cranes . . ." Among the Volga Bulgars, Ibn Fadlan found a strange custom: When they observe a man who excels through quickwittedness and knowledge, they say: "for this one it is more befitting to serve our Lord." They seize him, put a rope round his neck and hang him on a tree where he is left until he rots away.

Commenting on this passage, the Turkish orientalist Zeki Validi Togan, undisputed authority on Ibn Fadlan and his times, has this to say: "There is nothing mysterious about the cruel treatment meted out by the Bulgars to people who were overly clever. It was based on the simple, sober reasoning of the average citizens who wanted only to lead what they considered to be a normal life, and to avoid any risk or adventure into which the "genius" might lead them." He then quotes a Tartar proverb: "If you know too much, they will hang you, and if you are too modest, they will trample on you." He concludes that the victim 'should not be regarded simply as a learned person, but as an unruly genius, one who is too clever by half". This leads one to believe that the custom should be regarded as a measure of social defence against change, a punishment of non-conformists and potential innovators. (In support of his argument, the author adduces Turkish and Arabic quotations in the original, without translation – a nasty habit common among modern experts in the field.) But a few lines further down he gives a different interpretation: Ibn Fadlan describes not the simple murder of too-clever people, but one of their pagan customs: human sacrifice, by which the most excellent among men were offered as sacrifice to God. This ceremony was probably not carried out by common Bulgars, but by their Tabibs, or medicine men, i.e. their shamans, whose equivalents among the Bulgars and the Rus also wielded power of life and death over the people, in the name of their cult. According to Ibn Rusta, the medicine men of the Rus could put a rope round the neck of anybody and hang him on a tree to invoke the mercy of God. When this was done, they said: "This is an offering to God." Perhaps both types of motivation were mixed together: 'since sacrifice is a necessity, let's sacrifice the trouble-makers".

Human Sacrifice

We shall see that human sacrifice was also practised by the Khazars – including the ritual killing of the king at the end of his reign. We may assume that many other similarities existed between the customs of the tribes described by Ibn Fadlan and those of the Khazars.

PART 10

It took the Caliph's mission nearly a year (from June 21, 921, to May 12, 922) to reach its destination, the land of the Volga Bulgars. The direct route from Baghdad to the Volga leads across the Caucasus and Khazaria – to avoid the latter, they had to make the enormous detour round the eastern shore of the "Khazar Sea", the Caspian. Even so, they were constantly reminded of the proximity of the Khazars and its potential dangers.

A characteristic episode took place during their sojourn with the Ghuzz army chief (the one with the disreputable underwear). They were at first well received, and given a banquet. But later the Ghuzz leaders had second thoughts because of their relations with the Khazars. The chief assembled the leaders to decide what to do: The most distinguished and influential among them was the Tarkhan; he was lame and blind and had a maimed hand. The Chief said to them: "These are the messengers of the King of the Arabs, and I do not feel authorized to let them proceed without consulting you." Then the Tarkhan spoke: "This is a matter the like of which we have never seen or heard before; never has an ambassador of the Sultan travelled through our country since we and our ancestors have been here. Without doubt the Sultan is deceiving us; these people he is really sending to the Khazars, to stir them up against us. The best will be to cut each of these messengers into two and to confiscate all their belongings." Another one said: "No, we should take their belongings and let them run back naked whence they came." Another said: "No, the Khazar king holds hostages from us, let us send these people to ransom them."

They argued among themselves for seven days, while Ibn Fadlan and his people feared the worst. In the end the Ghuzz let them go; we are not told why. Probably Ibn Fadlan succeeded in persuading them that his mission was in fact directed against the Khazars. The Ghuzz had earlier on fought with the Khazars against another Turkish tribe, the Pechenegs, but more recently had shown a hostile attitude; hence the hostages the Khazars took.

The Khazar menace loomed large on the horizon all along the journey. North of the Caspian they made another huge detour before reaching the Bulgar encampment somewhere near the confluence of the Volga and the Kama. There the King and leaders of the Bulgars were waiting for them in a state of acute anxiety. As soon as the ceremonies and festivities were over, the King sent for Ibn Fadlan to discuss business. He reminded Ibn Fadlan in forceful language ("his voice sounded as if he were speaking from the bottom of a barrel") of the main purpose of the mission to wit, the money to be paid to him 'so that I shall be able to build a fortress to protect me from the Jews who subjugated me". Unfortunately that money – a sum of four thousand dinars – had not been handed over to the mission, owing to some complicated matter of red tape; it was to be sent later on. On learning this, the King – "a personality of impressive appearance, broad and corpulent" – seemed close to despair. He suspected the mission of having defrauded the money: "What would you think of a group of men who are given a sum of money destined for a people that is weak, besieged, and oppressed, yet these men defraud the money?" I replied: "This is forbidden, those men would be evil." He asked: "Is this a matter of opinion or a matter of general consent?" I replied: "A matter of general consent."

Gradually Ibn Fadlan succeeded in convincing the King that the money was only delayed, (Apparently it did arrive at some time, as there is no further mention of the matter). but not to allay his anxieties. The King kept repeating that the whole point of the invitation was the building of the fortress "because he was afraid of the King of the Khazars". And apparently he had every reason to be afraid, as Ibn Fadlan relates: The Bulgar King's son was held as a hostage by the King of the Khazars. It was reported to the King of the Khazars that the Bulgar King had a beautiful daughter.

He sent a messenger to sue for her. The Bulgar King used pretexts to refuse his consent. The Khazar sent another messenger and took her by force, although he was a Jew and she a Muslim; but she died at his court. The Khazar sent another messenger and asked for the Bulgar King's other daughter. But in the very hour when the messenger reached him, the Bulgar King hurriedly married her to the Prince of the Askil, who was his subject, for fear that the Khazar would take her too by force, as he had done with her sister. This alone was the reason which made the Bulgar King enter into correspondence with the Caliph and ask him to have a fortress built because he feared the King of the Khazars.

It sounds like a refrain. Ibn Fadlan also specifies the annual tribute the Bulgar King had to pay the Khazars: one sable fur from each household in his realm. Since the number of Bulgar households (i.e., tents) is estimated to have been around 50000, and since Bulgar sable fur was highly valued all over the world, the tribute was a handsome one.

PART 11

What Ibn Fadlan has to tell us about the Khazars is based – as already mentioned – on intelligence collected in the course of his journey, but mainly at the Bulgar court.

Unlike the rest of his narrative, derived from vivid personal observations, the pages on the Khazars contain second-hand, potted information, and fall rather flat. Moreover, the sources of his information are biased, in view of the Bulgar King's understandable dislike of his Khazar overlord - while the Caliphate's resentment of a kingdom embracing a rival religion need hardly be stressed.

The narrative switches abruptly from a description of the Rus court to the Khazar court: Concerning the King of the Khazars, whose title is Kagan, he appears in public only once every four months. They call him the Great Kagan. His deputy is called Kagan Bek; he is the one who commands and supplies the armies, manages the affairs of state, appears in public and leads in war. The neighbouring kings obey his orders. He enters every day into the presence of the Great Kagan, with deference and modesty, barefooted, carrying a stick of wood in his hand. He makes obeisance, lights the stick, and when it has burned down, he sits down on the throne on the King's right. Next to him in rank is a man called the K-nd-r Kagan, and next to that one, the Jawshyghr Kagan. It is the custom of the Great Kagan not to have social intercourse with people, and not to talk with them, and to admit nobody to his presence except those we have mentioned. The power to bind or release, to mete out punishment, and to govern the country belongs to his deputy, the Kagan Bek.

It is a further custom of the Great Kagan that when he dies a great building is built for him, containing twenty chambers, and in each chamber a grave is dug for him. Stones are broken until they become like powder, which is spread over the floor and covered with pitch. Beneath the building flows a river, and this river is large and rapid. They divert the river water over the grave and they say that this is done so that no devil, no man, no worm and no creeping creatures can get at him. After he has been buried, those who buried him are decapitated, so that nobody may know in which of the chambers is his grave. The grave is called "Paradise" and they have a saying: "He has entered Paradise". All the chambers are spread with silk brocade interwoven with threads of gold. It is the custom of the King of the Khazars to have twenty-five wives; each of the wives is the daughter of a king who owes him allegiance. He takes them by consent or by force. He has sixty girls for concubines, each of them of exquisite beauty.

Ibn Fadlan then proceeds to give a rather fanciful description of the Kagan's harem, where each of the eighty-five wives and concubines has a "palace of her own", and an attendant or eunuch who, at the King's command, brings her to his alcove "faster than the blinking of an eye. After a few more dubious remarks about the "customs" of the Khazar Kagan (we shall return to them later)

Ibn Fadlan at last provides some factual information about the country: The King has a great city on the river Itil [Volga] on both banks. On one bank live the Muslims, on the other bank the King and his court. The Muslims are governed by one of the King's officials who is himself a Muslim. The law-suits of the Muslims living in the Khazar capital and of visiting merchants from abroad are looked after by that official. Nobody else meddles in their affairs or sits in judgment over them.

Ibn Fadlan's travel report, as far as it is preserved, ends with the words: The Khazars and their King are all Jews. (This sounds like an exaggeration in view of the existence of a Muslim community in the capital. Zeki Validi accordingly suppressed the word "all". We must assume that "the Khazars" here refers to the ruling nation or tribe, within the ethnic mosaic of Khazaria, and that the Muslims enjoyed legal and religious autonomy, but were not considered as "real Khazars".) The Bulgars and all their neighbours are subject to him. They treat him with worshipful obedience. Some are of the opinion that Gog and Magog are the Khazars.

PART 12

Ihave quoted Ibn Fadlan's odyssey at some length, not so much because of the scant information he provides about the Khazars themselves, but because of the light it throws on the world which surrounded them, the stark barbarity of the people amidst whom they lived, reflecting their own past, prior to the conversion. For, by the time of Ibn Fadlan's visit to the Bulgars, Khazaria was a surprisingly modern country compared to its neighbours.

The contrast is evidenced by the reports of other Arab historians, (The following pages are based on the works of lstakhri, al- Masudi, Ibn Rusta and Ibn Hawkal [see Appendix II].), and is present on every level, from housing to the administration of justice. The Bulgars still live exclusively in tents, including the King, although the royal tent is "very large, holding a thousand people or more".26 On the other hand, the Khazar Kagan inhabits a castle built of burnt brick, his ladies are said to inhabit "palaces with roofs of teak",27 and the Muslims have several mosques, among them "one whose minaret rises above the royal castle". In the fertile regions, their farms and cultivat ed areas stretched out continuously over sixty or seventy miles. They also had extensive vineyards. Thus Ibn Hawkal: "In Kozr [Khazaria] there is a certain city called Asmid [Samandar] which has so many orchards and gardens that from Darband to Serir the whole country is covered with gardens and plantations belonging to this city. It is said that there are about forty thousand of them. Many of these produce grapes." The region north of the Caucasus was extremely fertile. In AD 968 Ibn Hawkal met a man who had visited it after a Russian raid: "He said there is not a pittance left for the poor in any vineyard or garden, not a leaf on the bough . . . [But] owing to the excellence of their land and the abundance of its produce it will not take three years until it becomes again what it was." Caucasian wine is still a delight, consumed in vast quantities in the Soviet Union.

However, the royal treasuries' main source of income was foreign trade. The sheer volume of the trading caravans plying their way between Central Asia and the Volga-Ural region is indicated by Ibn Fadlan: we remember that the caravan his mission joined at Gurganj consisted of "5000 men and 3000 pack animals". Making due allowance for exaggeration, it must still have been a mighty caravan, and we do not know how many of these were at any time on the move. Nor what goods they transported – although textiles, dried fruit, honey, wax and spices seem to have played an important part. A second major trade route led across the Caucasus to Armenia, Georgia, Persia and Byzantium.

A third consisted of the increasing traffic of Rus merchant fleets down the Volga to the eastern shores of the Khazar Sea, carrying mainly precious furs much in demand among the Muslim aristocracy, and slaves from the north, sold at the slave market of Itil. On all these transit goods, including the slaves, the Khazar ruler levied a tax of ten per cent. Adding to this the tribute paid by Bulgars, Magyars, Burtas and so on, one realizes that Khazaria was a prosperous country – but also that its prosperity depended to a large extent on its military power, and the prestige it conveyed on its tax collectors and customs officials.

Apart from the fertile regions of the south, with their vineyards and orchards, the country was poor in natural resources. One Arab historian (Istakhri) says that the only native product they exported was isinglass. This again is certainly an exaggeration, yet the fact remains that their main commercial activity seems to have consisted in re-exporting goods brought in from abroad. Among these goods, honey and candle-wax particularly caught the Arab chroniclers' imagination. Thus Muqaddasi: "In Khazaria, sheep, honey and Jews exist in large quantities." 30 It is true that one source – the Darband Namah – mentions gold or silver mines in Khazar territory, but their location has not been ascertained. On the other hand, several of the sources mention Khazar merchandise seen in Baghdad, and the presence of Khazar merchants in Constantinople, Alexandria and as far afield as Samara and Fergana.

Thus Khazaria was by no means isolated from the civilized world; compared to its tribal neighbours in the north it was a cosmopolitan country, open to all sorts of cultural and religious influences, yet jealously defending its independence against the two ecclesiastical world powers. We shall see that this attitude prepared the ground for the coup de theatre – or coup d'tat – which established Judaism as the state religion.

The arts and crafts seem to have flourished, including haute couture. When the future Emperor Constantine V married the Khazar Kagan's daughter (see above, section 1), she brought with her dowry a splendid dress which so impressed the Byzantine court that it was adopted as a male ceremonial robe; they called it tzitzakion, derived from the Khazar-Turkish pet- name of the Princess, which was Chichak or "flower" (until she was baptized Eirene).

"Here," Toynbee comments, "we have an illuminating fragment of cultural history."31 When another Khazar princess married the Muslim governor of Armenia, her cavalcade contained, apart from attendants and slaves, ten tents mounted on wheels, "made of the finest silk, with gold-and silver-plated doors, the floors covered with sable furs. Twenty others carried the gold and silver vessels and other treasures which were her dowry".32 The Kagan himself travelled in a mobile tent even more luxuriously e quipped, carrying on its top a pomegranate of gold.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Say what is on your mind, but observe the rules of debate. No foul language is allowed, no matter how anger-evoking the posted article may be.

Thank you,

TruthSeeker